Emily Floyd

Melbourne

2017

Displayed 2017 at Art Gallery of New South Wales

Emily Floyd

Born 1972, Melbourne. Lives and works Melbourne

Emily Floyd works in sculpture, print-making and public installation. Her work takes shape at the intersections where sculpture meets public space and design collides with social crisis. It embraces elements of expanded sculpture and a range of print media and typographic artefacts, including the poster and the manifesto. Floyd renegotiates the possibility of public address, critically engaging an increasingly diverse and unpredictable viewership in debate. Her work gestures towards new forms of sociality for which the artwork can serve both as provocation and as venue.

Artist text

by Anneke Jaspers

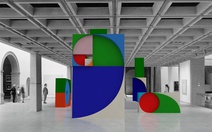

Kesh Alphabet (2017) draws into dialogue the language of abstraction and the coded visual system of the alphabet. Eschewing the familiar lines of Latin script, Emily Floyd’s sculptural installation references a fictional alphabet described by the feminist science-fiction writer Ursula Le Guin in her 1985 novel Always Coming Home, an anthropological study of the future Kesh society that interweaves prose, verse and diagrams. The book’s coda includes an infographic of the 32-sign Kesh alphabet – the basis of Le Guin’s invented language and, in turn, her attempt to imagine an alternative social model that is matriarchal, secular, environmentally sustainable and classically socialist.

Kesh Alphabet spells out the Kesh noun banhe, which translates into English as ‘inclusion’, ‘insight’ and ‘female orgasm’. In the gallery, however, one first encounters this word in the abstract, untranslated and further de-familiarised through Floyd’s typography and the work’s dispersed composition. Formally, the vivid prisms invoke oversized children’s building blocks, referencing Floyd’s interest in historical movements that explored design for play, such as Bauhaus, and perhaps also the ‘blocks of shaped and sanded mill-ends’ and ‘lettered wooden tablets’ that Kesh children used as toys. (1) Arranged as a permeable field, these monumental letters mark out a discrete venue for gathering and activity within the expansive Central Court of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW).

In part, the work riffs on the pastiche of architectural styles that collide in this space, which functions as a kind of Greek agora beyond the AGNSW’s neoclassical facade, incongruously dominated by the rigid geometric design of a modernist ceiling grid. During early research, Floyd also observed the gender dynamics at play in this zone of heightened social and pedagogic activity. On the one hand, she saw the masculine character of the architecture echoed in the dominance of male artists in the collection displays; conversely, the audience inhabiting the Central Court was overwhelmingly female. She came to think of this female presence as ‘the Gallery’s circulatory system’, the ‘soft’ life force animating its ‘hard’ infrastructure. (2)

Kesh Alphabet embodies this feminine principle, extending up into the ceiling grid as a disruptive gesture that literalises Floyd’s desire to ‘recolonise the space’ with a feminist perspective. In this regard, the work reflects her interest in the legacies of feminist design, which emerged during the women’s movement of the 1970s as a means of producing inclusive, democratic spaces for protest and self-organisation. Floyd’s choice of the Kesh word banhe registers her desire for feminist change more emphatically, affirming a strictly female space of experience and pleasure, which Le Guin aligns linguistically – not by coincidence – with a shift in perception and the redistribution of agency. Writ large in the heart of an indisputably patriarchal institution, the work is offered as ‘a spell or invocation’. Untranslated and hence freighted with potential, it conjures a different future while reminding us, as Le Guin does in Always Coming Home, that ‘language is not meaning’ in itself but a system through which world views are shaped and expressed. (3)

Notes

(1) Ursula Le Guin, Always coming home, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2001, pp.480, 482

(2) Unless otherwise noted, all quotes are from interviews between the artist and author, August–October 2016.

(3) Le Guin, op.cit., p.413.