Léuli Eshrāghi

Meanjin/Brisbane and Tiohtià:ke/Montreal

2023

Displayed 2023 at Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Léuli Eshrāghi

Born 1986, Yuwi Country

Lives and works between Meanjin/Brisbane and Tiohtià:ke/Montreal

Léuli Eshrāghi is a multidisciplinary artist, curator and researcher of Sāmoan, Persian and Cantonese ancestry who creates performance, time, installation and text-based works that affirm Indigenous presence and power. Eshrāghi has exhibited widely, nationally and internationally. Their work is held in the Royal Bank of Canada (Toronto/Sydney) and Fonds régional d’art contemporain (Nantes) collections among others. Recent exhibitions include: A Clearing in the Forest, Tate Modern, London (2022); Embodied Knowledge, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (2022); An Ocean in Every Drop, Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai (2022); Au fil des îles, archipels, Centre d’exposition de l’Université de Montréal (2022); NIRIN: 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020); Leaving the Echo Chamber: Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019); duo exhibition Projections: Léuli Eshrāghi and Jessica Karuhanga for Queer City Cinema Festival, Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina (2021); and solo exhibition La fin est toujours le début d’autre chose | The end is where we start from in Quand la nature ressent / Sensing Nature, MOMENTA | Biennale de l’image, Diagonale, Montréal (2021). Eshrāghi holds a Doctor of Philosophy (Curatorial Practice) from Monash University, Melbourne. They are Curatorial Researcher in Residence at the University of Queensland Art Museum; and Curator of TarraWarra Biennial 2023: ua usiusi faʻavaʻasavili at TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville.

Photograph: Rhett Hammerton

Image courtesy the artist

Artist text

by James Gatt

Léuli Eshrāghi embraces Indigenous relation and futurism, illuminating precolonial possibilities for human existence. They renounce colonial borders, reimagining international connections as ʻo le vā o motu (Sāmoan for ‘the space that relates between islands’), and eschew the heteronormative nuclear family in favour of queer kinship. Amidst institutional prospects of decolonisation, Eshrāghi’s socio-political, collaborative, and speculative works envisage Indigenous futurity in a context still enduring imperialist consequences.

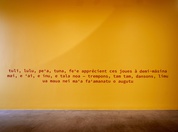

In their text, video, and textile installation afiafi (2023), Eshrāghi revives the queer heterogeneity of interpersonal connection, traditional among Indigenous peoples despite widespread Christian suppression. From the gender hybridity of muxes in Mexico to the non-binary māhū of Hawai’i, the same-sex companionship of the Māori takatāpui, and the non-monogamous Zo’é of Amazonia and Ladakhis of the Himalayas, ‘Indigenous sexualities were never straight: ranging from cross-dressing to homo-affective families, they are as diverse as the peoples who practice them.' (1) Unlike Western futurism, (2) Indigenous futurisms (3) embrace temporal and social multiplicity, a process of ‘discovering how personally one is affected by colonisation, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post–Native Apocalypse world.' (4)

afiafi is the fourth work in Eshrāghi’s ongoing series Siapo viliata o le atumotu (2020–). It debuts a multilingual poetry collection, two-channel video, photographic wallpaper, and a series of custom ʻie (sarongs). ‘Afiafi’ means day, afternoon, evening, and fire in Sāmoan, symbolising lifecycles, pleasure, and renewal. Social interactions with queer Indigenous kin are central to the work. Roaming like a mobile community centre between Australia, Hawai’i, Canada, and Europe in 2022 and 2023, Eshrāghi has woven together conversations concerning desire, kinship, and time. This is a ‘social practice’ of ‘socialist’ intent; terms mobilised in the deep empathy of community production. The wallpaper documents a collaborative performance at Aupuni Space, Honolulu, establishing afiafi as a space for cultural exchange. This bonding gesture carries through Eshrāghi’s ʻie, textiles traditionally exchanged in ceremonies for affirming and strengthening community wellbeing. (5) ‘Ie hold bodies, wrapping them for dress and cushioning them for seated gathering. Eshrāghi’s designs are based on motifs of Indigenous intellectual and cultural property shared across Tonga, Fiji, and Sāmoa. The accompanying video records Eshrāghi and collaborators in ceremony in the dark, bringing present, real-time activation to the embodied ritual of Indigenous storytelling.

Eshrāghi’s poems, collectively titled Lumanaʻiga a motu (Island Traditions) (2022–ongoing), solemnly voice their experiences and aspirations as a non-binary/faʻafafine person of Sāmoan, Persian, and Cantonese ancestry, addressing genealogy, sexuality, loss, and the future. Eshrāghi practises non-binarisation beyond the nomenclature of imposed gender identity, writing its essential diversity into their work for richer possibilities of relation- and future-building. Written in Sāmoan, English, and French, the collection’s voice is cosmopolitan, mapping Eshrāghi’s multicultural influences with polyphonic verse. ‘In my writing are expressions of my Sāmoan faʻafafine gender, queer sexuality, and defense of worlds independent of Christian colonialisms, enforced heteropatriarchies, carceral capitalisms, and illiteracies in Indigenous histories.' (6)

In the advent of artificial intelligence, afiafi debunks the normalisation of virtual, commodified, and surveilled relations, asking whose values determine society and its future, and finding constructive tenderness in queer and Indigenous sociality. Though the language of diversity is more accessible than ever, Eshrāghi models uses for real enfranchisement. After all, what use is egalitarianism if it serves only to stratify communities; if it ironically fetishises, exoticises, or politicises the peoples it claims to liberate?

(1) Manuela Lavinas Picq and Josi Tikuna, ‘Indigenous sexualities: Resisting conquest and translation’, in Caroline Cottet and Manuela Lavinas Picq (eds.), Sexuality and Translation in World Politics, E-International Relations Publishing, 2019, retrieved October 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/120/417043/taking-the-fiction-out-of-science- fiction-a-conversation-about-indigenous-futurisms/

(2) See Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, ‘The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism’, in Alex Danchev (ed.), 100 Artists' Manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists, Penguin Books, London, 2011.

(3) See Grace Dillon and Pedro Neves Marques, 'Taking the Fiction Out of Science Fiction: A Conversation about Indigenous Futurisms’, e-flux Journal, 2021, retrieved October 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/120/417043/taking-the-fiction-out-of-science- fiction-a-conversation-about-indigenous-futurisms/

(4) Grace Dillon, Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction, University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, 2012, p.10.

(5) UNESCO, ‘’Ie Samoa, fine mat and its cultural value’, retrieved October 2022, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/-ie-samoa-fine-mat-and-its-cultural-value-01499.

(6) Léuli Eshrāghi, ‘Introduction’, in Lumanaʻiga a motu (Island Traditions), working draft accessed digitally.

Artist's acknowledgements

afiafi (2023) was made in Naarm with Spacecraft Studio (Stewart Russell, Danica Miller, Ana Maria Antunes), and in Honolulu with kekahi wahi (Sancia Miala Shiba Nash, Drew Kahu‘āina Broderick), Kaliko Aiu, Maile Aluli Meyer, Donnie Cervantes, Lise Michelle Childers, Daniel Croix, Marika Emi, Hercules Goss-Kuehn, Mele Hamasaki, Reise Kochi, Josh Tengan, Nanea Lum, Madi, and Aaron Wong.

Ua pa‘i ‘ia kēia hana no‘eau ma kēia mau wahi: Pu‘u ‘ōhi‘a a me Ka‘alawai, Kona, O‘ahu, Ka Pae ‘Āina o Hawai‘i. Mahalo nunui i ka ‘ohana Potter a me ka ‘ohana Cervantes-Morehart.

afiafi was commissioned by Aupuni Space (Honolulu), the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (Tallawoladah), the University of Tasmania (nipaluna), and Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (Baden-Baden), and developed during residencies in Paris at the Cité internationale des arts (April–July 2022) supported by Institut français and the Embassy of France in Australia, and in Honolulu at Aupuni Space and TRADES A.i.R. (January–February 2023) supported by the Laila Twigg-Smith Art Fund.