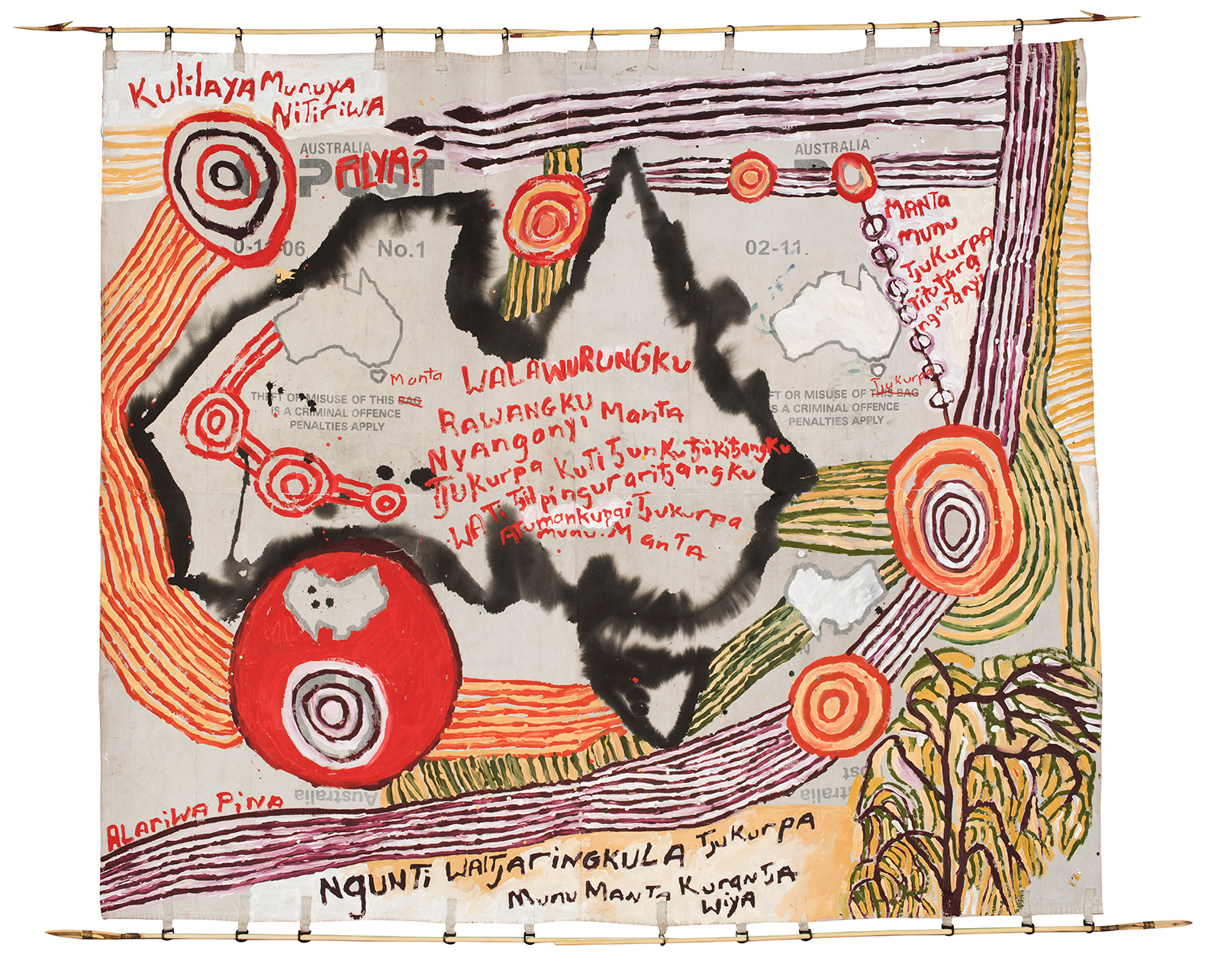

Kunmanara (Mumu Mike) Williams

Mimili, South Australia. Pitjantjatjara, Southern Desert region

2019

Displayed 2019 at Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Kunmanara (Mumu Mike) Williams

1952–2019. Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, South Australia. Lived and worked Mimili, South Australia. Pitjantjatjara, Southern Desert region

Kunmanara (Mumu Mike) Williams was born in 1952 between Kenmore Park and Pukatja in South Australia. He learnt to read and write in Pitjantjatjara and English at the Ernabella Mission School, before working as a cattle stockman. After returning to the APY Lands, Williams worked as a carpenter building houses in Ernabella. He was active in the APY Land Rights movement that led to the signing of the Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act 1981 and the return of land to Anangu. Williams was a renowned ngangkari (healer), pastor of the Mimili community church and political activist. He became a celebrated senior artist, addressing issues including governance, sustainable land management, the protection of sacred heritage sites, and the rights of traditional owners.

Photograph: Rhett Hammerton

Artist text

by Henry Skerritt

Maruku Tjukurpa titutjara alatjitu ngaranyi tjitji malatja malatja tjutaku kulu Tjukurpa kunpu alatjitu Kamanta ngunti walytjaringanyi munu manta Tjukurpa kurani. Kunta wiyangku alatjitu.Manta nyanga miilmiilpa tjara wantima tjawantja wiyangku. Kulinma, munuya pitjala nyangama wati tjilpi tjutangku atunytju kanyilpai. Ruta palyantja wiyangku manta miilmiilpa wanungku nganampa Tjukurpa kurani. Kamantaku Tjukurpa wiya. Nganampa manta. Nganampa Tjukurpa. Nganampa ara. Tjukurpa miilmiilpa tjara.

Black skinned Aboriginal people have always had powerful Tjukurpa Dreaming law and have passed it down through generations since time began. The government simply cannot claim ownership of this land and must never destroy cultural heritage sites. The shame of it. Do not destroy sacred sites or dig up the land around them. Listen, if you come here, you must accept that the law of our land is under the control of our senior men. Do not plan to build roads in the vicinity of sacred sites, because of the risk of destroying Tjukurpa. The government doesn’t have Tjukurpa. This is our land. Our Tjukurpa. Our cultural heritage. Our Tjukurpa is sacred. (1)

Born in 1952 between Kenmore Park and Pukatja (Ernabella), Mumu Mike Williams is a highly cosmopolitan artist. His life has seamlessly melded his obligations as a traditional custodian and working as a stockman, pastor and carpenter. He has traversed his ancestral Country in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands and has travelled the world, visiting Europe, America, India and the Middle East. For Williams these seemingly disparate worlds are all encompassed within a philosophy of Tjukurpa that is much larger than any imposed human boundaries.

Over the past three years, Williams has embarked on a series of paintings on repurposed canvas mailbags. In using government property as his canvas, Williams draws attention to the conflict between Commonwealth and Anangu law. Williams is a big-picture artist, and his work for The National 2019 is as metaphorically big as they come. Here, ‘Australia’ is rendered larger than the outmoded modernist ideal of a nation-state – it is a radiating haze, an energy field that both envelops and exceeds European cartographic vision. As the lines of Williams’ paintings push to the edge of his makeshift ‘canvases’ they extend out into the world. Unrestricted by the boundaries of states or territories, Tjukurpa connects every point in space and time. Unlike the postal service, Tjukurpa does not need government authorisation; it is eternal, indelible and unbreakable.

The impassioned text writ large in Pitjantjatjara across Williams’ paintings is not a demand for literal translation: it is a demand for recognition. For Walter Benjamin the aim of good translation was not the transferral of information but the acceptance of the kinship of languages – of our shared human urge to signify. (2) Even without understanding Pitjantjatjara, the urgency of Williams’ messages is unmistakable. These are words that demand respect. They demand the recognition of the enduring power of Tjukurpa; of the prior occupation of these lands; of the hundreds of languages spoken on our continent; of the persistence and power of Indigenous cultures; and, perhaps most significantly, they demand the recognition of our shared humanity. These demands are bigger than any government or nation: they are global missives sent out with the precision of a well-aimed spear, more powerful than anything that could be contained within in a mailbag.

Notes

(1) Pitjantjatjara text (translated by Linda Rive) from Mumu Mike William’s Kamantaku Tjukurpa wiya. (The Government doesn’t have Tjukurpa.) (2018), included in The National 2019.

(2) Walter Benjamin, ‘The task of the translator’ in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, New York, 1968, p.72.